Syracuse University professor Colleen Heflin attributes success to more than just hard work. Sometimes it’s about being in the right place at the right time.

“I had a doctoral advisor in college who was an income poverty expert,” recalls the professor of public administration and international affairs in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. “He asked me if I wanted to work on a food insecurity project—one of the first of its kind in the United States. Until then, I hadn’t given much thought to the subject nor its relationship with public policies.”

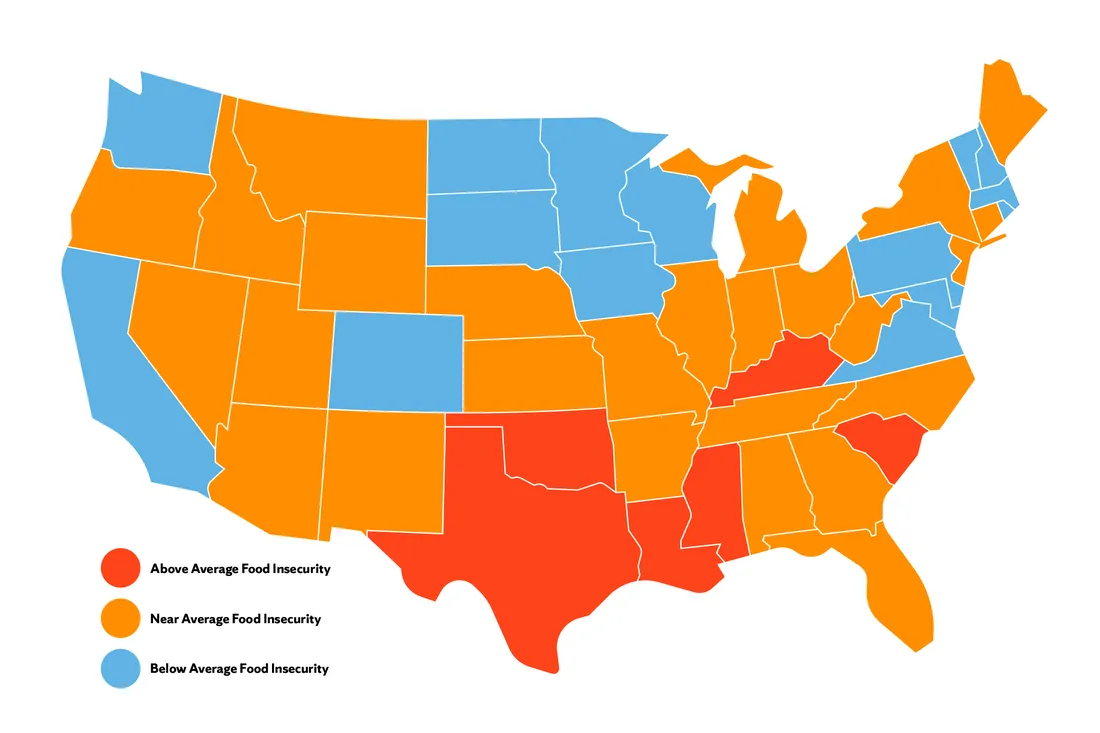

Heflin has since become a leading authority on food insecurity, which, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), negatively impacts more than 47 million Americans.

More than 47 million Americans have limited or uncertain access to adequate food.

In anticipation of World Hunger Day (May 28), she’s reminded of the ubiquitousness of food insecurity—that it transcends race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Small wonder that food insecurity afflicts nearly a third of the global population.

“There are many factors that limit our access to safe, nutritious food,” says Heflin, whose expertise includes nutrition and welfare policy. “These factors contribute to a cycle of poor health, economic hardship and limited opportunities that’s difficult to break without assistance of some kind.”

We recently caught up with Heflin to discuss her research and learn more about her work.

What causes food insecurity?

The availability of household economic resources. Where you live, urban versus rural. The policies that affect you. The kinds of community support you have. Your level of physical mobility and access to transportation. How close you live to a grocery store.

The causes in the United States are different from those in other countries, which, in many cases, include war, climate change and food shortages.

Studies show that while most U.S. households are food secure, a surprising number of them—about 18 million—cannot access adequate food due to lack of money and resources.

Are any of these factors within our control?

To a degree. For instance, our physical health affects our performance in school, which, in turn, influences where we live and work.

At the same time, there are cumulative risk factors, like poverty and systemic racism, that some of us are born into. They’re often intertwined with other complex issues—chronic disease, mental illness, barriers to access—that are difficult to overcome without assistance.

A research and policy scholar, Heflin is particularly interested in the link between food insecurity and psychological distress. “Poor mental health limits our ability to secure adequate and nutritious food, perpetuating a vicious cycle,” she says.

How is your research making an impact?

Professor Michiko Ueda-Ballmer and I study the link between food insecurity and psychological distress, like anxiety and depression. Poor mental health limits our ability to secure adequate and nutritious food, perpetuating a vicious cycle.

I’ve also authored papers about WIC [Women, Infants and Children], a federal nutrition assistance program benefiting low-income pregnant, postpartum and breastfeeding women as well as infants and children under the age of five.

We know there’s a spike in food insecurity when children age out of WIC but aren’t old enough to access school meals. It should be an easy fix, from a policy standpoint, and my research helps in this regard.

Heflin regularly collaborates with the Maxwell X Lab in the Center for Policy Research, the Aging Studies Institute, and the Center for Aging and Policy Studies.

Is it safe to say that you design interventions that become policy?

Broadly speaking, yes. I recently did a project with the Maxwell X Lab that was funded by the USDA. [The lab is a program of the Maxwell School’s Center for Policy Research, where Heflin is a senior research associate.]

We studied something called “administrative churn,” where beneficiaries of social programs, like SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program], temporarily lose their benefits due to administrative or procedural issues. I helped design a system that enabled more people to stably receive benefits.

“Learning about food insecurity is the first step in addressing it,” says Heflin, who also encourages students to donate to a food pantry or volunteer at a soup kitchen.

Studies show that food insecurity disproportionately affects single mothers and children. What about older adults?

Some of my research involves the Aging Studies Institute and the Center for Aging and Policy Studies, where I respectively serve as a faculty affiliate and research affiliate. A frequent collaborator of mine is Madonna Harrington Meyer [a University Professor of sociology], with whom I’ve authored Food for Thought. This forthcoming book looks at food insecurity among older adults, a phenomenon exacerbated by social isolation and a lack of support systems.

I’ve also worked with older adults at the Syracuse VA Medical Center, which is one of the nation’s best veterans’ hospitals. My research on veterans with sociology professors Janet Wilmoth and Andrew London led to my invitation to testify before Congress on military and veteran food insecurity.

More recently, I’ve designed and evaluated a Food Is Medicine pilot program, which provides medically tailored grocery delivery for 250 Syracuse-based veterans. [The project is co-sponsored by The Rockefeller Foundation with support from the New York Health Foundation and Instacart.] It’s a scalable solution for a large, important population.

Combating food insecurity requires a multipronged approach that addresses immediate needs and underlying systemic issues.

What else can we do?

You can drop off donations to any food pantry or volunteer for a soup kitchen. This kind of work is a great way to get to know your community—individuals and families alike.

Of course, learning about food insecurity is the first step in addressing it. There’s a lot of great information online, including policy briefs on the Maxwell School website. Each brief is a precise, easy-to-understand summary of faculty research findings, intended for policymakers, journalists, practitioners and lay people.

I’ve written quite a few of these briefs and am excited to see them prompt sustained, meaningful change.