If you visit Governors Island in New York Harbor in the spring, you will see something extraordinary: an orchard where every tree flowers in a multitude of different-colored blossoms. Come back in the summer and fall, and you’d see an array of stone fruit varieties—peaches, plums, cherries and nectarines—ripening in each tree.

This is The Open Orchard, an artwork by Syracuse University College of Visual and Performing Arts professor Sam Van Aken. Each tree in the orchard is a living sculpture composed through the ancient agricultural practice of grafting, by which pieces from different trees are attached to one another and become incorporated into a single living plant. The Open Orchard produces 200 varieties of heirloom stone fruits that used to be commonplace in the gardens, backyards and orchards of New York State. Over the past century, climate change and our dependence on industrial agriculture has led to the overwhelming dominance of a few varieties bred for durability and appearance, precipitating the near extinction of thousands of others.

The scientific solutions to address climate change are already out there—we know what we need to do. Where art becomes a vehicle for change is by giving people an experience that allows them to access their own thoughts and opinions.

Sam Van Aken, associate professor of studio arts

“I’m interested in helping students define their art practice and build a foundation that leads to experimentation,” says Van Aken, who encourages an expansive definition of art and art making.

While the orchard, which was commissioned by the Trust for Governors Island and opened in April 2022, is the first of its kind, Van Aken has planted over 40 multi-grafted trees around the country. Each one bears varieties of stone fruit endemic to the area where it grows. His preservation of these diverse and regionally specific fruits has brought him into a range of conversations around issues of sustainability and climate change—even with the U.S. Department of Defense, which is tracking food insecurity provoked by climate change as a domestic threat and is interested in the genetic bank Van Aken has revived.

Climate change—and specifically the way human communities and cultures respond to its effects—is in line with themes Van Aken explores repeatedly in his work: nexuses of culture and nature, the relationship of perception and reality, and our reliance on the metaphysical to explain phenomena beyond our understanding or control. He’s explored these ideas in works ranging from weather modification projects to installations inspired by dynamics among technology, media and belief.

Grafting, an ancient technique that fuses disparate plants so they grow as one, is the only way to pass genetically identical fruit from one tree to the next.

Rooted in Environmental Awareness

Van Aken traces his interests to growing up on a dairy farm in Pennsylvania, where his family produced their own food and made most of their own clothes. Farming, he says, instills an acute awareness of how powerfully climate—as experienced in droughts and hailstorms, cold snaps and severe wind—can determine our fates. “You reach a certain point when you’ve done everything you can possibly do to manage these conditions—you reach the end of the capacities of technology,” he says. “And that’s when you turn to faith, to prayer, to hoping for miracles.”

Van Aken’s multi-grafted fruit trees preserve heirloom stone fruit varieties endemic to the area where the trees grow.

But when Van Aken first conceived of the Tree of 40 Fruit, it wasn’t as a statement about climate change or even agriculture. He was curious about the idea of transubstantiation—when the outer appearance of something stays the same while its essential identity changes—and wanted to create a tree evocative of that concept. He chose the number 40 because of its significance in various religious mythologies.

It was the unanticipated challenge of finding 40 varieties of fruit that took the project in a new direction, ultimately one highlighting a dangerous result of industrial food production: a cultural disconnect from the environment. “Much of the population is so separated from where their food originates that it’s an abstraction,” Van Aken says. And without a lived understanding of the consequences climate change can have, he explains, it doesn’t register as a priority.

Shaping a Sustainable Culture

This is where art can play a role. “The scientific solutions to address climate change are already out there—we know what we need to do,” he says. “Where art becomes a vehicle for change is by giving people an experience that allows them to access their own thoughts and opinions.” Van Aken believes experiences can inspire major shifts in understanding and action. “Look at how much effort it takes to grow even a single tomato. Anyone who goes through that process—on a farm or in their backyard garden—is going to have a deeper appreciation of the forces of weather,” he says. “We tend to think of our reality as this very static and solid thing. But it is continuously changing. It’s something that we can shape.”

The multi-grafted fruit trees and related projects are visceral experiences that invite people to imagine a different relationship with the environment. Because fruit seeds are genetic variations of the trees that bear them, grafting is the only way to get exact replicas of fruit. Some of the varieties Van Aken has propagated can be traced back thousands of years—branches passed from plant to plant, across continents and centuries—thanks to the symbiotic relationships at the heart of agriculture.

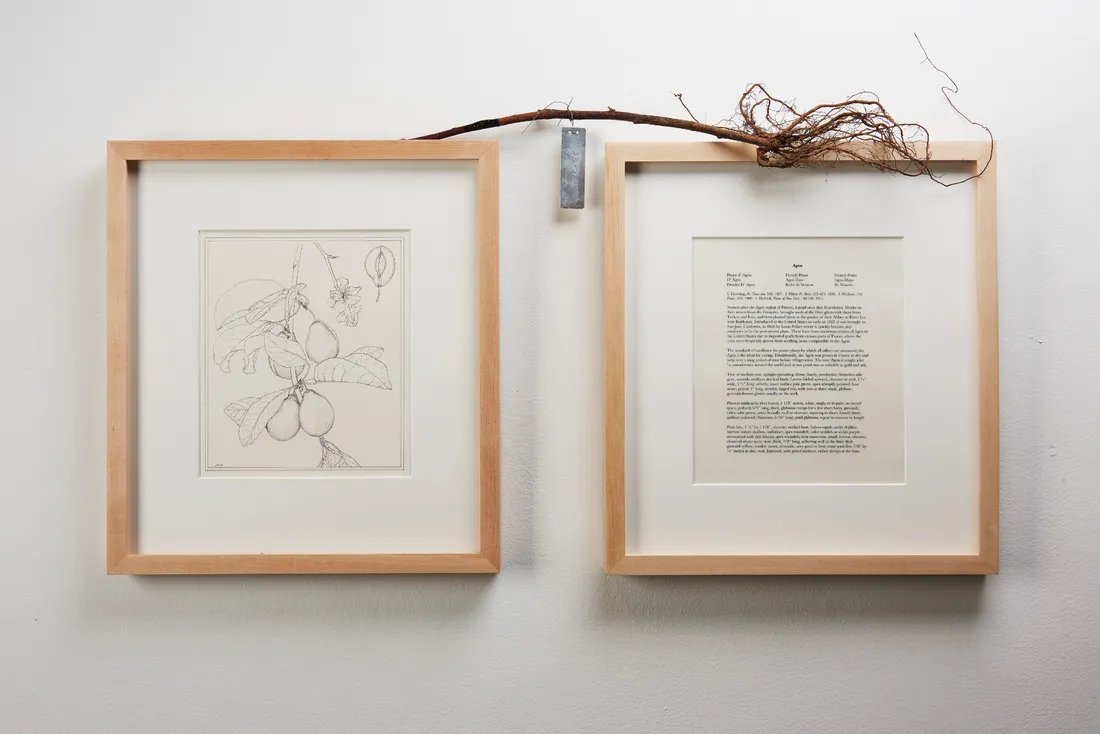

Van Aken creates hand-painted etchings of heirloom fruit varieties, using techniques that are centuries old, and chronicles their origin stories.

Van Aken describes cultivated fruit trees as cultural objects. The Open Orchard is based on old European models of communal orchards, which were traditionally tended by and for the benefit of entire villages, and a similar practice followed by the Lenni Lenape, the indigenous inhabitants of New York City. The project includes a forthcoming book of hand-painted etchings of each variety along with its origin story; how its fruits were used, prepared or preserved; and preindustrial techniques for tree care. Also, Van Aken is collaborating with Green Thumb, New York City Parks and Recreation’s community garden initiative, to distribute 100 trees to community gardens around the city, bringing fruit varieties back to neighborhoods where they used to grow.

Van Aken jokes that that the market for his art is school kids on field trips as often as it is art galleries. And that’s OK with him. Reflecting on the direction he sees his work taking, he recalls the wisdom of the 19th-century pomologist Charles Downey. “‘You don’t plant trees for yourself. You plant them for the future,’” Van Aken quotes. “That’s been resonating with me lately. When you plant a tree, it likely won’t hit its maturity until after you’re dead. We plant them for someone else—and that’s how we shape the future.”