OK, here’s a test. What’s the last animal you saw? Do you remember its size, shape or color?

Now, think about the last plant you saw.

If you’re like most people, you probably don’t recall the plant as vividly as the animal. This is because of our tendency to ignore or overlook our green neighbors—a phenomenon known as plant blindness.

Studies show that plant blindness is on the rise. And while it might seem harmless, the disconnection has consequences for us and our environment.

At Syracuse University, faculty and students are challenging this trend. Across the disciplines, they’re exploring how the natural world improves the way we think, feel, live and define our sense of place.

Professors Cary Peñate (far left) and Romita Ray (center) with their student curators in Central Park. From left: Isabel V. Maine-Torres ’24; Gwendolyn Sonnenschein ’25; Sidney Hanson ’25; Audrey Ingram ’25; Sevasti Nistazos ’25; Quentin Labunski ’24; Arielle Feldman ’25; and Charlotte Dupree ’25. Not pictured: Mackenzie Law ’25.

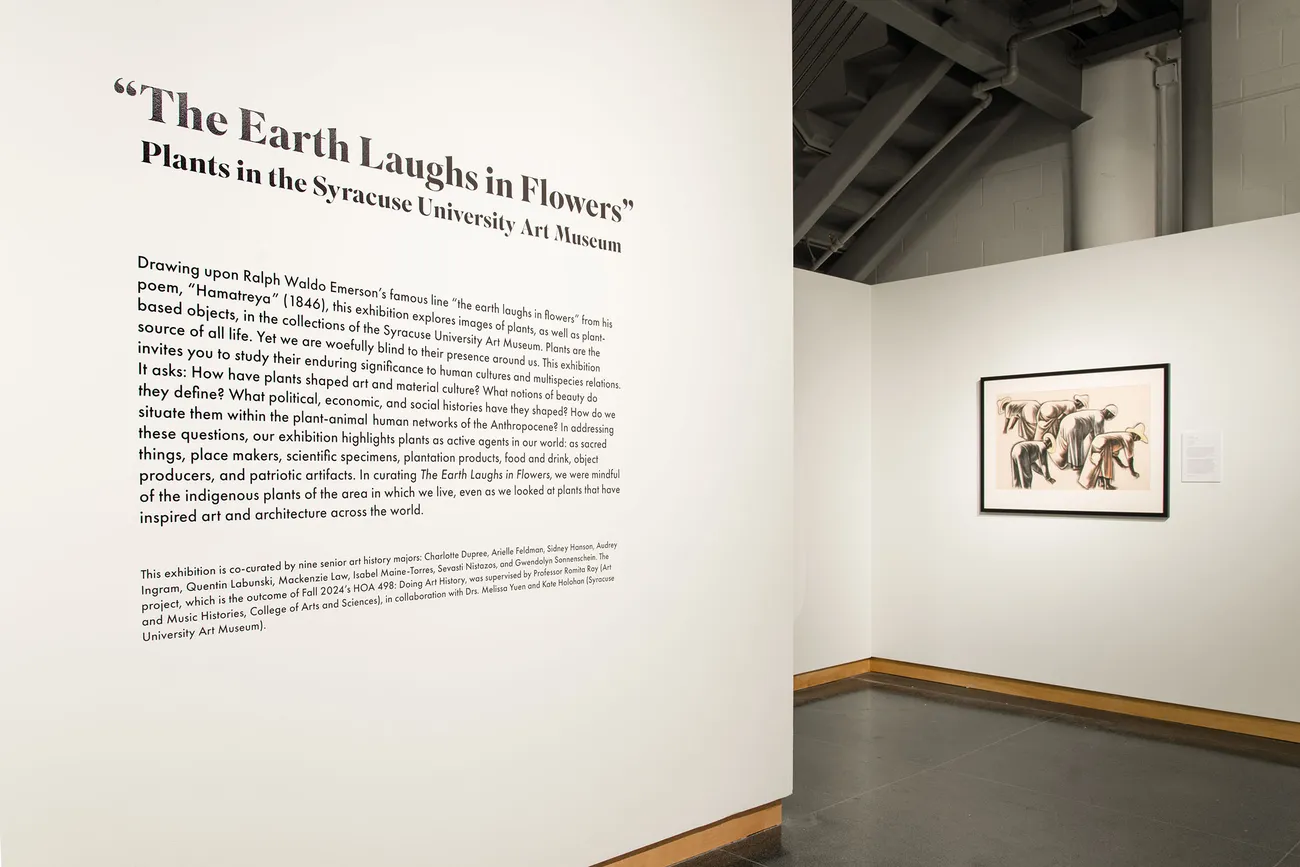

Art historian Romita Ray is helping lead the charge. She’s the faculty supervisor of The Earth Laughs in Flowers, a student-curated exhibition at the Syracuse University Art Museum (on display through May 10) that highlights plant imagery and plant-based objects.

The show marks the culmination of a senior seminar for nine art history majors in the College of Arts and Sciences. Working closely with Ray and museum curators Melissa Yuen and Kate Holohan, the students have acquired hands-on training in curatorial research and public engagement.

“Plants play a significant role in art and culture,” says Ray, an associate professor of art and music histories. “They also convey a range of meaning, from religious symbolism to political commentary.”

The title, The Earth Laughs in Flowers, stems from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poem Hamatreya—a nod to his appreciation for nature’s gifts, especially their restorative powers.

“Emerson was a gardener and a philosopher,” Ray continues. “While he didn’t explicitly reference plant blindness in his writing”—the term wasn’t coined until 1999—“Emerson understood how plants contribute to our health and wellness.”

Facing the Flora—and Ourselves

The Earth Laughs in Flowers includes Words That Come Before All Else—Thanksgiving Address (2021), by Ronni-Leigh Goeman ’84, G’91, G’96 and her husband, Stonehorse. The Native American basket is made from black ash, sweet grass, moose hair and moose antler. (Photo by Jiayue Yu G’26)

Plant blindness manifests in subtle but significant ways. Forgetting to water a houseplant. Walking past trees without noticing them. Underestimating the emotional boost we get from green spaces. That’s exactly what The Earth Laughs in Flowers wants to reverse.

“We lose something when we stop noticing it,” Ray cautions. “Our exhibition invites us to slow down and listen to what plants are telling us.”

Melissa Yuen, the museum’s curator, believes plant blindness may be tied to our fractured attention spans and screen-dominated lives. “Plant blindness could be the result of humanity focusing on itself at the expense of the natural world. Engaging with our natural surroundings is an idea that extends to works of art.”

In addition to teaching Ray’s students how to write exhibition labels, Yuen researched and wrote about two prints that were recently donated to the University. All the pieces in the exhibition, she explains, are from the University’s extensive holdings, one of the largest in academia.

The exhibition includes (from left to right) works by 20th-century American painter Harold Newton and 19th-century French artist Théodore Rousseau as well as two prints from Robert John Thornton’s Temple of Flora, a highly regarded, 19th-century botanical illustration book. (Photo by Jiayue Yu G’26)

No surprise that The Earth Laughs in Flowers—and human-nature interaction, in general—can leave participants spellbound. Activities like gardening, forest bathing and relaxing in green spaces are found to reduce stress, enhance our mood and boost cognitive function.

This is because plants don’t just sustain life; they also “make it better,” Ray observes.

And yet, most of our food in the West comes from just a handful of plant species. “There’s so much untapped potential in plants,” she says, adding that more than 14,000 species are considered edible and nutritious. “Recognizing the healing power of plants helps heal ourselves and the environment.”

Humanities in Bloom

“We’re telling plant stories through data and metaphor,” says Ray, citing, as an example, Sweet Grapes (1928), by American sculptor Harriet Whitney Frishmuth. In the background is Conrad Kiesel’s Young Woman with Roses (1890). (Photo by Jiayue Yu G’26)

The Earth Laughs in Flowers is more than an exhibition. It’s plant humanities in action, a growing interdisciplinary field blending environmental science with art, literature, history and cultural studies.

“We’re telling plant stories through data and metaphor. This helps us move from passive observers to active stewards of our environment,” says Ray, who serves on the advisory committee of the Plant Humanities Initiative at Dumbarton Oaks, Harvard University’s research institute in Washington, D.C.

Running through May 10 at the Syracuse University Art Museum, The Earth Laughs in Flowers features plant-inspired paintings, sculptures and decorative arts. “Plants are part of our emotional ecosystem,” Ray adds. (Photo by Jiayue Yu G’26)

For Gwendolyn Sonnenschein ’25, working on the exhibition has been a revelation. Her research into Conrad Kiesel’s Young Woman with Roses (1890) gave her fresh insights into 19th-century art, where nature was often a source of inspiration and interest.

“I learned a lot about the symbolic and sensory power of flowers,” she says, noting that plants are more than decorative, that they also reflect a desire to connect with our natural surroundings, like the E.M. Mills Rose Garden in Syracuse’s Thornden Park.

Another standout is Sweet Grapes (1928), a small bronze sculpture by American sculptor Harriet Whitney Frishmuth. Fruit, in this context, is a metaphor for growth and vitality, reminding us that plants can mirror our pursuit of beauty and evolution in unexpected ways.

“Plants are part of our emotional ecosystem,” says Ray, whose own research is steeped in the science and culture of Indian tea. “If we learn how to connect with plants, they give us so much in return.”