- William Burke ’25 creates digital maps to identify areas at risk for childhood lead poisoning in the City of Syracuse.

- His research is funded by a SOURCE Bridge Award, supporting faculty-led undergraduate research at Syracuse University.

- Outlawed decades ago, lead-based products and materials persist in older, low-income neighborhoods and pose significant health risks to children.

Are maps outdated? “No way,” exclaims William Burke, a senior in Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. “They do more than help us get around. Working with maps develops skills that can be applied to other areas of our life.”

Skills that Might Save Lives

William Burke ’25 uses innovative mapping techniques to identify areas at risk for childhood lead poisoning in Syracuse. “It persists in older, lower-income neighborhoods,” he says.

Burke found this out last spring after receiving a Bridge Award from the Syracuse Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Engagement (SOURCE). The award enabled him to use a technique called geospatial mapping to identify areas at risk for childhood lead exposure in the City of Syracuse.

Broadly speaking, geospatial mapping combines location data with different types of descriptive information. The result is an interactive map whose data can be curated for myriad purposes—like identifying sources of lead exposure to jumpstart appropriate preventive measures.

“Prior to being banned in the 1970s, lead was used in many household products and materials, like paint and plumbing, because of its malleability and resistance to corrosion,” Burke says. “It still persists in many older, lower-income neighborhoods.”

While people of all ages unknowingly ingest or inhale lead particles, children are especially vulnerable because, even in trace amounts, lead can stunt their brain development.

A double major in geography and environment, sustainability and policy, Burke spent most of last year addressing these issues with Peng Gao, professor and chair of the Geography and the Environment Department.

Gao joins a growing number of Syracuse faculty conducting research into lead poisoning, including Sandra Lane and Robert Rubenstein (public health and anthropology as well as anthropology, respectively), Brooks Gump (public health) and David Larsen (public health).

“Professor Gao recognized my interest in public health and the environment,” says Burke, who presented his findings at a SOURCE fair in December. “I’ve been able to develop skills that will further my career and make a difference in the lives of others.”

A Complex Problem

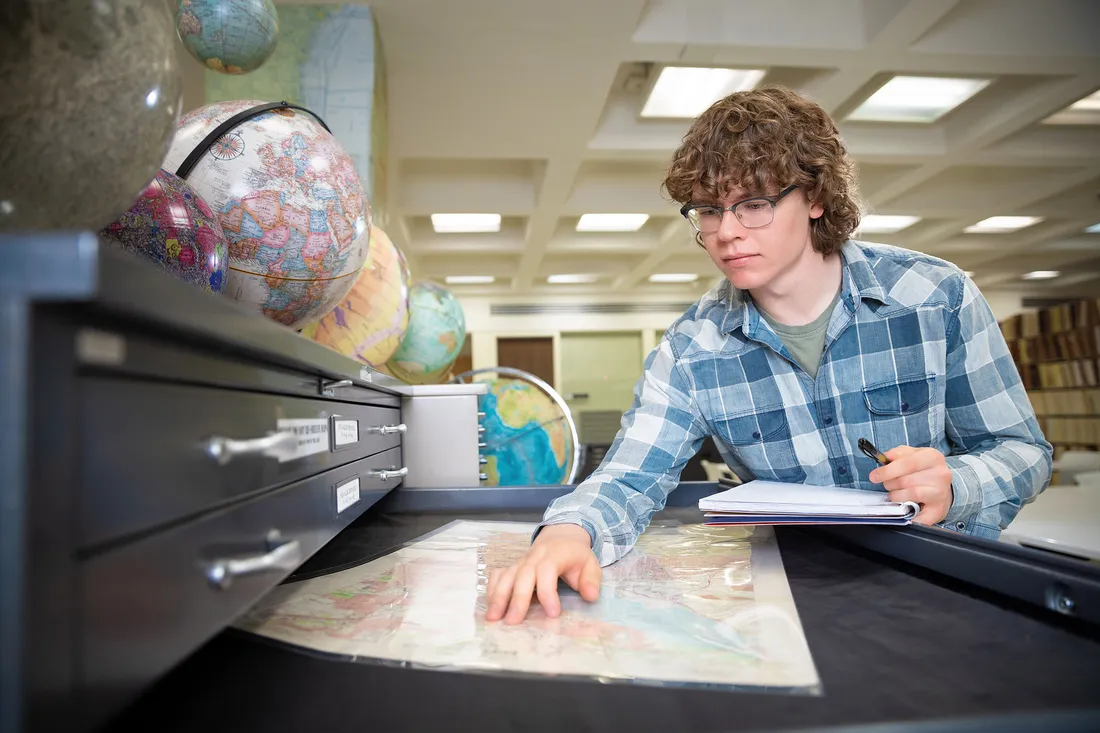

Burke in the Map Room of Bird Library. He received a SOURCE Bridge Award to further his study of geospatial mapping.

Burke connected with Gao last year, when the professor asked for his assistance with a project about watersheds in South America.

“He was a natural,” recalls Gao, praising Burke’s ability to manage data describing the location and characteristics of natural and human-made elements.

Gao then invited him to work on a new, nonfunded lead poisoning study. Drawing on public health surveillance data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Onondaga County Health Department, the duo mapped the City of Syracuse—from small census blocks, which are areas bounded by roads and property lines; to block groups, containing several hundred housing units; to large census tracts, encompassing some 4,000 people.

Lead poisoning is preventable, explains Burke, a double major in geography and environment, sustainability and policy. He’s excited to see other students build on his research and develop appropriate preventive measures.

Burke employed two geostatistical methods to manage the data. One was interpolation, which helped him estimate data for areas too small to be directly measured, like a residential property in a census block.

The other was geographically weighted regression, allowing Burke to examine the spatial relationship between different variables, like the link between socioeconomic factors and brain development and structure.

“We went a step further by looking at how lead can potentially lead to neurotoxicity,” says Burke, noting that lead also can damage the central nervous system, kidneys and reproductive system.

Another concern is what experts call the “lead-crime hypothesis”—the potential connection between childhood lead exposure and aggressive tendencies. “Behavioral and emotional issues show up even with low exposure [to lead],” Burke adds. “It’s a complex problem.”

Finding His Voice

“Lead can potentially lead to neurotoxicity,” says Burke, whose SOURCE-funded research was supervised by Peng Gao, professor and chair of the Geography and the Environment Department.

Burke insists that for all its dire consequences, lead poisoning is preventable. He and others in the field are convinced that a proactive, multipronged approach is the answer. Education. Advocacy. Safety measures.

Gao is excited for other students to build on Burke’s work. “Will did an excellent job of performing geospatial analyses of children in different [geographic] units,” Gao says. “He also learned a complex tool on his own that allowed him to get robust results.”

Burke has since worked with other professors, including Jane Read (geography and the environment) and Elizabeth Carter (Earth and environmental sciences), on mapping projects that have benefitted clients like the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Micron Technology.

His goal is to win an environmental consulting job after graduation.

“My undergraduate research with SOURCE has helped me find my voice as a storyteller,” Burke says. “It’s also mapping my future as a geographer.”

Burke hopes to win an environmental consulting job after graduation. “My undergraduate research with SOURCE is mapping my future as a geographer,” he says.