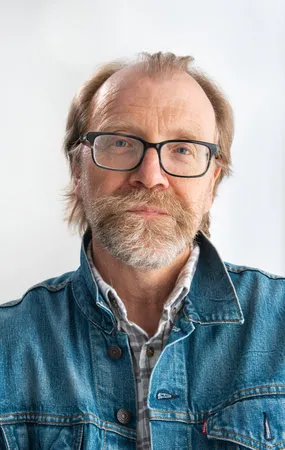

Professor George Saunders G’88 is the author of 11 books, including Lincoln in the Bardo and Tenth of December. “He is the best short-story writer in English—not ‘one of,’ not ‘arguably,’ but the best,” says fellow professor Mary Karr.

Pairing classic short stories with analytical essays might sound daunting to some, but Syracuse University professor George Saunders G’88 has a knack for breaking down the “physics of form,” showing how fiction works.

One such example is rooted in an incident from 20 years ago, when Saunders was on a flight from Chicago to Syracuse. At one point, a seagull darted into one of the engines, causing the aircraft to plummet. Panic swept through the cabin. After sharing a white lie with a passenger in attempt to comfort him, Saunders had an epiphany. Instead of trying to suppress his fear, he decided to embrace it. “I was brought back to myself by becoming myself,” he says.

Saunders describes this kind of radical acceptance, where fear turns into a superpower, as “moral transformation.” Leo Tolstoy wrestled with it 125 years earlier in his short story Master and Man. The author is part of a quartet of Russian Realists, including Anton Chekhov, Ivan Turgenev and Nikolai Gogol, whose fiction is on display in Saunders’ latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain.

A “master class on writing, reading and life,” the text draws on a popular course that Saunders, a New York Times bestselling author, has taught in the College of Arts and Sciences since his pivotal flight.

Storytelling is the most ancient human activity because it’s essentially what the brain does. It looks out at the world and offers us a scale model of what it sees—that’s the first draft—and then it starts amending the model with data—the revision.

Professor George Saunders

Saunders’ next story collection, Liberation Day, explores ideas of power, ethics and justice. “He’s becoming a little more gentle on the page, more forgiving, more earnest,” says Random House Publisher Andy Ward. (Photo by Zach Krahmer)

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain—a line from Gooseberries, the second short story in Chekhov’s “Little Trilogy”—is about as close as most people get to studying writing with Saunders, a faculty member of the esteemed graduate program in creative writing, one of the nation’s oldest, most distinguished full-residency programs of its kind.

A graduate of the Colorado School of Mines, Saunders became interested in literature while working as a field geophysicist in Indonesia. “I wanted to see the world, and the rigor and logic of engineering eventually got into my writing,” he recalls. Initially, Saunders was into Euro-American Modernists, like Steinbeck and Hemingway, but he soon became enamored of the Golden Era of Russian literature (c. 1820-80). The way that Russian authors probed the human experience while under the threat of censorship mystified him. Never mind that they anticipated Western Modernism by several decades.

“The Russians saw fiction as a moral-ethical tool, rather than something decorative,” says Saunders, who also likes how they asked big, existential questions, such as “How are we supposed to be living?”, “What should we value?” and “What is truth?”

These questions have taken on a renewed sense of urgency during the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War—events that Saunders compares to living on the back of a sleeping tiger. (“Once in a while, the tiger wakens, and we suffer and grow,” he says, paraphrasing the ancient Buddhist axiom.) A cursory glance at the news might suggest fiction’s recent surge in popularity and why more mainstream magazines are hiring writers like Saunders to put a fresh spin on things.

“Storytelling is the most ancient human activity because it’s essentially what the brain does. It looks out at the world and offers us a scale model of what it sees—that’s the first draft—and then it starts amending the model with data—the revision,” explains Saunders, whose nonfiction has appeared in The New Yorker, GQ, Esquire, McSweeney’s and The New York Times Magazine. “Storytelling is not something we learn to do; it’s who we are.”

Saunders in conversation with fellow professor and acclaimed novelist Jonathan Dee in Hendricks Chapel.

Blending Reality and Unreality

Before the meteoric success of his 11 books, before his recognition as one of the world’s most influential people (Time magazine) and before his routine appearances on The Colbert Report, All Things Considered and The Diane Rehm Show, all Saunders wanted to do was write.

The soft-spoken Midwesterner enrolled at Syracuse having seen enough of the world to star in a Jack Kerouac novel. (By then, he also had worked as a roofer, doorman and slaughterhouse “knuckle-puller.”) A People magazine article about novelist Jay McInerney G’86 persuaded him to study creative writing. “Before that, I had never even heard of an M.F.A. program, so I applied to a couple universities,” Saunders says.

I try to bring students into a zone where they question their own creative choices.

Professor George Saunders

Syracuse won out, thanks in part to then M.F.A. director Tobias Wolff, who was mesmerized by Saunders’ “unusual perspectives.” The legendary author took Saunders under his wing and helped him hone his idiosyncratic style. Today, they remain close friends. The same goes for Saunders’ wife, novelist Paula Saunders G’87, a fellow classmate to whom he became engaged after three weeks of dating.

While working as a technical writer in Rochester, New York, Saunders published his first story collection, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, in 1996. The book has become a cult classic, continually winning over new readers. They include Jonah Evans G’22, one of Saunders’ students, who considers the title story—a romp about a dystopian, Civil War-themed amusement park—a comedic masterstroke.

“As a writer, George Saunders blends reality with unreality. As a teacher, he holds us accountable to specificity. If we veer away from it, he pulls us back,” Evans says. “There are no boundaries with him, and the layers are complex. He inspires me to write about whatever I want, plainly, weirdly and freely.”

“Storytelling is not something we learn to do; it’s who we are,” says Saunders, whose latest bestseller, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, pairs Russian short stories with analytical essays.

Finding the Inner Person

After CivilWarLand, Saunders’ career kicked into high gear. Returning to Syracuse in 1997—this time, as a professor—afforded him time to research, write and give public readings. His works include Lincoln in the Bardo, a highly experimental, debut novel that won the 2017 Man Booker Prize (and whose acclaimed audiobook featured a star-studded cast of 166 narrators), and Tenth of December, a National Book Award finalist. He also has launched a Substack newsletter, whose readership is north of 35,000.

He inspires me to write about whatever I want, plainly, weirdly and freely.

Jonah Evans G’22

No one was more surprised than Saunders when, in 2013, a convocation speech he gave to graduating Arts and Sciences students went viral. His remarks became the basis for Congratulations, by the Way, a college graduation book that has won the hearts of readers and nonreaders alike.

“George reminds us that our lives on Earth may be fleeting, but that doesn’t mean they lack meaning or that our actions don’t matter,” says longtime editor Andy Ward, who is finalizing Saunders’ next story collection, Liberation Day. “As George likes to say, we should err in the direction of kindness whenever possible.”

Saunders isn’t big on labels, but he considers himself a teacher first, a writer second. Ergo his guiding of hundreds of graduate students, many of whom have gone onto careers in publishing, journalism, communications and academia. “My students remind me that talent is with us in a million forms. Reading and critiquing their work allow me to look past external indicators and find the inner person,” says the former MacArthur and Guggenheim fellow, who splits time between campus and his home in Santa Cruz, California.

Every class with Professor Saunders feels like an energetic conversation between fellow artists who care about their work and its effect on the world. He’s made me realize that art matters, and that all of us need to keep making it.

Theodore “Teddy” Allor G’22

Theodore “Teddy” Allor G’22 was among some 700 people who applied for—and got—one of the M.F.A. program’s 12 coveted spots in 2019. With Saunders’ help, he plans to publish a novel and earn a Ph.D. in creative writing. “Every class with Professor Saunders feels like an energetic conversation between fellow artists who care about their work and its effect on the world,” says the aspiring professor. “He’s made me realize that art matters, and that all of us need to keep making it.”

Following the Voice

Saunders’ advice usually revolves around the revision process, the “thousands of micro-choices” that ultimately reveal the kind of writer someone is. More than just cleaning up or correcting text, revising is a systematic approach to storytelling, he clarifies. “I try to bring students into a zone where they question their own creative choices.”

Lean, muscular prose is his calling card, and approaching it “brick by brick” engenders a sense of economy. And impact. Before workshopping anything, Saunders’ students are required to come up with a “one-line, Hollywood pitch” about what they’re writing. “This way, we follow the voice—letting the characters drive the narrative, instead of fitting the characters into it,” says Allor, noting that the simpler the story, the more believable it is.

Graduate student JR Fenn G’22 echoes these sentiments, calling Saunders a “narrative genius.” Her favorite stories of his are Winky, notable for its alternating point-of-view structure, and Sticks, a 392-word lesson about parental fallibility. “Professor Saunders tells me that when I’m writing, there’s a genius-child in the room. My job is to be very quiet and still and to get out of the way so that the child can come out,” says the Rochester-based writer.

Fenn echoes the long-held belief that Saunders is nothing short of a literary polymath, someone who can “mind-read a story to illuminate a universe of possibilities.” Small wonder that he has proven his mettle as a short- and long-form novelist, an essayist, a journalist, even a children’s author. For Saunders’ money, the short story is the most demanding—and elusive—of forms. Like a joke, it works, or it doesn’t. There’s no middle ground. “Everything in it has an immediate purpose,” he continues. “The fun is finding out what the form will permit. And what I’m willing to risk in the process.”

Providing Maximum Bumpage

Saunders has built a career on risk and reward. Back in 2010, his short story Escape from Spiderhead appeared in The New Yorker. Imbued with didactic themes, the piece reflected his growing interest in exaggerated fiction and the “we-are-what-we-think” movement. “I provide a wild ride for the reader,” he told The New Yorker’s Deborah Treisman. “I’m like a river-rafting guide who’s been paid a bonus to purposely steer my clients into the roughest water possible.”

Escape from Spiderhead soon attracted the attention of Deadpool writers Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick, who adapted the story into the Netflix film Spiderhead, premiering June 17. Set in the not-so-distant future, the movie focuses on a group of convicts involved with an experimental drug-testing program. “Just as drugs do in real life, the ones in the story literally change who the characters are, affecting their emotions and abilities,” says Saunders, noting that the film stars Chris Hemsworth, Jurnee Smollett and Miles Teller.

I provide a wild ride for the reader. I’m like a river-rafting guide who’s been paid a bonus to purposely steer my clients into the roughest water possible.

Professor George Saunders

Ensuring “maximum bumpage” is what Saunders gleaned from his professors at Syracuse, and it's what he imparts to his own students. For him, writing is more than a skill or job; it’s a calling. “If you go in the direction of the biggest bump, the thematics of the story change, but that’s not my decision to make,” he concludes. “The energy of the story dictates everything.”

This story was updated on June 7, 2022.